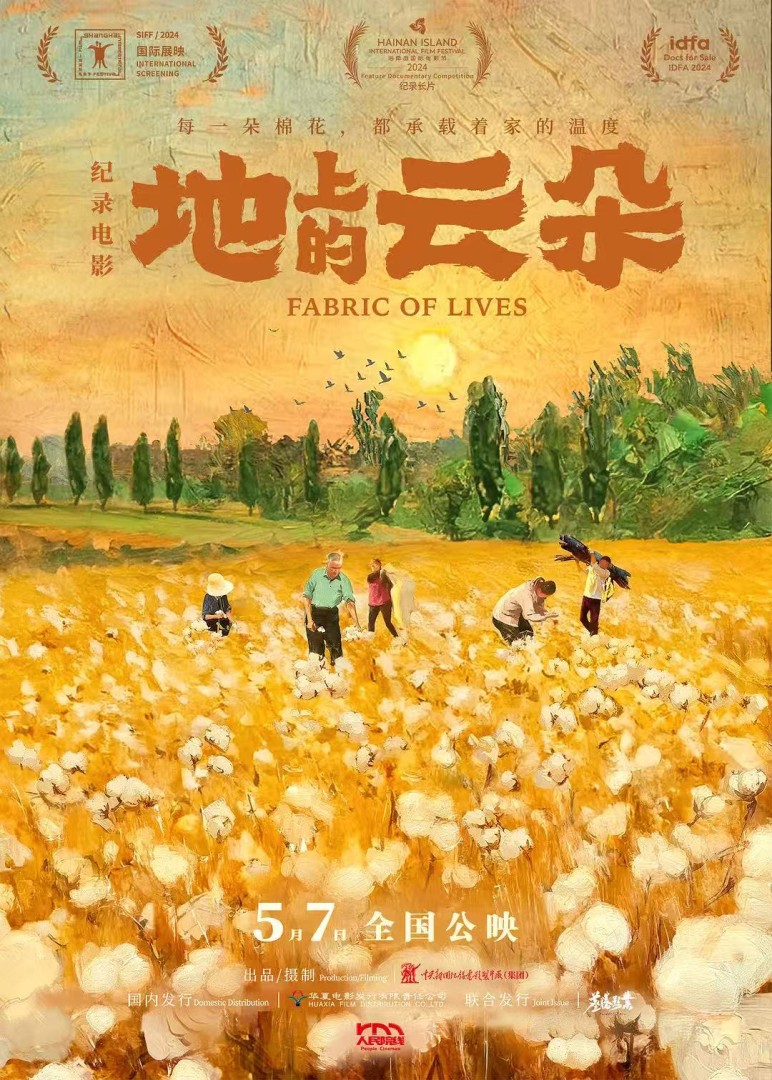

In the early summer of 2025, Fabric of Lives slipped quietly into Chinese theaters. It didn’t make box office waves like “Nezha 2,” nor did it whisk viewers away to the rainy, witty English countryside of the latest season of “Clarkson’s Farm.” There are no animated spectacles here, no winking British banter—this documentary takes the gentlest possible route, burrowing deep into the heart of China’s land. Like a soft breeze over the fields, it brushes the screen with subtlety, yet leaves a lasting, tender resonance.

Directed by Liu Guoyi, Fabric of Lives turns its lens on two ordinary cotton-farming families in southern Xinjiang’s Awati County—one Uyghur, one Han. With remarkable restraint, the film chronicles the rhythms of their agricultural year and the texture of their daily lives. This is not a film that clamors for attention with grand themes. Instead, it offers a quietly profound portrait of rural China, capturing the most genuine and delicate threads of everyday existence.

Beyond Stereotypes, Into the Heart of Daily Life

For many urban viewers, Xinjiang conjures up vast landscapes, exotic cuisine, or a kind of distant romanticism. Fabric of Lives purposefully sidesteps these visual clichés. The film is rooted almost entirely in cotton fields and villages, lowering its gaze to ground level to capture the sweat of labor, the warmth of family bonds, and the minutiae of daily life. The stories of the Aierken and Zhao Qiang families are stripped of heroics and melodrama—what remains is the honest cycle of planting, harvesting, and the constant negotiation with the land.

Director Liu employs the “Direct Cinema” approach—a documentary style that emerged in mid-20th-century North America, emphasizing minimal interference from the filmmaker and a pursuit of reality in its purest form. The crew lived alongside the farmers, sharing meals and routines, becoming nearly invisible members of the household, patiently waiting for meaningful moments to unfold naturally. There are no scripts, no staged interviews, no guiding narration—just the quiet observation of real life. This approach demands extraordinary sensitivity and patience, and relies on trust between filmmaker and subject. As a result, the people in the film never perform for the camera; viewers are drawn into their emotional currents and the pulse of their daily lives.

The film’s greatest strength lies in its attention to the ordinary: a mother and daughter carefully selecting a suitcase for college, haggling over the price; a father’s silence as he sends his daughter off to school; brief smiles and fatigue in the fields. These moments, unvarnished and unforced, are poetry in motion.

Universal Resonance in the Fields

Fabric of Lives offers an honest depiction of cotton harvesting, the advance of mechanization, and the economic realities facing Xinjiang’s farmers. The film does not attempt to answer or even address international debates about Xinjiang’s cotton; instead, it maintains an impartial, observational gaze, allowing viewers to draw their own conclusions. Its commitment to honesty and respect endures throughout.

What’s remarkable is that this dedication to local detail does not confine the film to a regional narrative. On the contrary, whether at home or abroad, Fabric of Lives has sparked broad emotional resonance. Chinese audiences see their own families reflected in its scenes: farewells, reunions, the anxious hope for a good harvest, the quiet dreams parents hold for their children. Overseas viewers, too, have been moved by the warmth of quotidian life depicted. At post-screening discussions, international audience members have remarked that, despite differences in geography, culture, or language, the attachment to the land, the anxiety over crop prices, and the gentle resilience of familial love are universal.

It is this unadorned realism and emotional honesty that bridge cultural divides, allowing the stories of ordinary cotton farmers to resonate worldwide. Whether in Xinjiang’s fields, the pastures of England, or the cornfields of America’s Midwest, the themes of land and family, hope and worry, are touchingly similar. As the director notes, “The truest empathy between people always emerges from the most specific details of daily life.”

Feedback from international festivals confirms the film’s universal appeal—audiences everywhere recognize themselves in the joys and anxieties of family, the uncertainty of harvest, and the shared burdens of life on the land.

Poetry and Unease in the Details

The film’s sensitivity to detail is extraordinary. Many scenes—deliberately understated—are shot through with both poetry and anxiety. Fabric of Lives never shies away from the hardships of labor: the toil of the cotton fields, income instability, and the uncertainties that weigh on every family’s future. One of the film’s most emblematic moments comes when a father asks his young son, “Do you want to be a farmer when you grow up?” The child’s silence is heavy, embodying the tension between land, destiny, and the pressures of modernization. This is not only a contemporary take on the age-old question of whether the next generation will stay with the land, but a question echoed in rural societies worldwide.

Yet, the film is equally attentive to tenderness. A mother sewing a new quilt for her daughter, a father bustling in the kitchen, idle family chatter at the table—these vignettes form a mosaic of millions of Chinese households. The cinematography is quietly beautiful: the cotton fields at sunset, doves on the rooftop, a folksong hummed during a break from work—all captured with a rustic, almost primordial grace. The director’s patient lens reveals subtle emotional shifts: a mother’s tears before her daughter leaves, the family sharing watermelon after the harvest, a father’s awkward but loving encouragement as he grills skewers for his children.

But this warmth never glosses over life’s difficulties. The film repeatedly shows farmers’ worries over price fluctuations, fears about the harvest, and anxieties about the future. Mechanization brings both relief from physical labor and the fracturing of traditional skills and community structures. As the younger generation leaves for cities and schools, what remains is not just the land, but the lingering attachment of parents and the evolving sense of self. The film’s candid depiction of the everyday never loses sight of the complex tension between land and fate, progress and continuity.

The quietly observed moments—those that might seem mundane—become footnotes of poetry and questions for the future. The film reminds us that what we take for granted as “ordinary” is often the vessel for generations of hope and struggle.

A Living Epic Spun from Cotton

Fabric of Lives has no celebrities, no sentimental soundtrack, and no sweeping narrative arcs. With the simplest of images, it tells stories of profound consequence. In an age of globalization and relentless urbanization, this film prompts viewers to reconsider the meaning of land, labor, family, and hope. It does not pretend to answer every question or take a definitive stance; instead, it chooses to accompany, to witness, and to understand—quietly.

More importantly, by following the thread of cotton, the film documents a way of life that is fiercely resilient. It records the daily realities of two families—one Uyghur, one Han—working and living on the same land, collaborating and watching over each other. The depiction of multiethnic coexistence is subtle and unforced, never reduced to symbolism or spectacle. What emerges is the most natural expression of kinship, friendship, and mutual support.

Fabric of Lives also refocuses our attention on agriculture and on rural communities and farmers too often marginalized by the sweep of urbanization. With its unflinching honesty, it reminds us that grain, cotton, and home—these seemingly ordinary things—are the bedrock of social stability and cultural continuity. The cotton fields are not merely sites of economic activity; they are the soil of memory, emotion, and identity.

Yet the film’s dual titles—Fabric of Lives in English and “Clouds on the Ground” in Chinese—reveal a layered poetic resonance. The English title evokes the interconnectedness of ordinary people’s destinies, woven together through labor, land, and family. It speaks to the resilience and dignity embedded in daily toil. Meanwhile, the Chinese title, “Clouds on the Ground,” offers a gentler, almost dreamlike metaphor: the cotton fields, from a distance, resemble clouds resting on the earth. This image not only captures the visual beauty of Xinjiang’s landscapes, but also suggests hope, softness, and the quiet aspirations that rise from the soil.

The interplay between these two titles reflects the film’s dual commitment: to document the tangible realities of rural life, and to honor the intangible yearnings, memories, and poetry that hover above it. The cotton on the land is at once the material of daily survival and the cloud of dreams that sustains families across generations.

Across these cloud-like fields, every inch of land bears the weight and warmth of life, allowing the world to witness the dignity of the ordinary. As one of the filmmakers put it: “With our images, we hope to harvest a cloud, and with it, a piece of happiness that belongs to ordinary Chinese people.” In the end, this documentary becomes a gentle yet powerful ballad—a living epic of land, family, multiethnic coexistence, and the tides of the times, quietly etched into the hearts of its audience.

By Wang Jiang (Deputy Dean, Institute of China’s Borderland Studies, Zhejiang Normal University)

Media Contact

Company Name: Institute of China’s Borderland Studies, Zhejiang Normal University

Contact Person: Wang Jiang

Email: Send Email

City: Jinhua

Country: China

Website: www.zjnu.edu.cn